Everything, from the props to the set, to the actors themselves, is labelled in Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Photo: The Finger Players.

“No silences or gaps, please,” playwright-director Chong Tze Chien says to the actors, 14 students on the cusp of graduation from Diploma in Theatre (English Drama) programme at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). They are all dressed in black and wearing face masks – the surgical kind, not theatrical – and panting slightly from the exertion of the run-through.

It’s just gone past noon on 7 Oct 2020, and it’s my first time attending a rehearsal of Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea in the NAFA Theatre Studio. As the production’s documenter, I observe and take notes from my vantage point in the last row of the house, surrounded by yellow-tape slashes on seats barred from use.

Although it’s cold in the theatre, and wearing a mask for an extended period of time isn’t comfortable, I am fuelled by my reverence for the play and its history, as well as a healthy curiosity about what is different about this restaging, and how the students prepared themselves for a professional production.

The students rehearsing a scene where the demons wreak havoc in the flat. Photo taken on 7 Oct 2020.

Tze Chien continues sharing his feedback with the students on the prologue of the show, a tightly choreographed sequence in which a multitude of characters traipse up and down a narrow L-shaped pathway marked out on the ground in white tape. The pathway represents the long common corridor of an HDB block of flats, skirting around the floor plan of a two-bedroom flat, the main setting of the play.

Devil is a triple bill of playlets, all about families living in an HDB block of flats. In the first playlet, a grandmother is desperately trying to get her grandson to buy over her flat before she dies. In the second playlet, a girl and her mother’s lecherous boyfriend are constantly at loggerheads. And in the third and final playlet, revelations of adultery and criminal activity threaten to tear a family apart. All three domestic feuds play out against the backdrop of the block’s residents voting for or against upgrading works by the government.

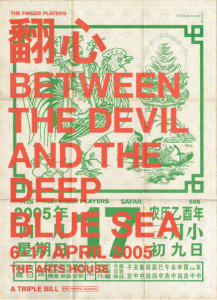

As Tze Chien runs through the rest of his notes, I note that it’s less than a month to the performance of Devil as the closing production of The Finger Players’ (TFP) Present/Future Season, presented in collaboration with NAFA. There won’t be an audience; Devil will be livestreamed over the Internet on 6 Nov.

Point of No Return

The last time Devil was performed was when it premiered in 2005. I wasn’t able to see it, and my only experience with the play had been as a published script. But what I did know was that Devil holds a huge significance in the history of TFP.

Tze Chien began writing what would eventually be Devil in the early 2000s. At the time, he could feel his time at The Necessary Stage (TNS), where he had been groomed as a playwright, was coming to end. But it wasn’t an easy realisation to arrive at.

“I was stuck artistically,” he admitted. “But I felt that whatever choice that I had to make at the time was a conundrum, in every possible way.”

The following year, he joined TFP as its Company Director to spearhead a new artistic direction for the company. TFP had been known as a puppetry company that produced children’s theatre performances; but at that juncture, the company wanted to venture into more mature content.

Tze Chien created Devil by revising a short play he had written while with TNS, and added two more. He also wrote in another defining feature of the play – its demons, wily creatures that creep out from the shadows to wreak havoc. Tze Chien explained that the demons satisfied TFP’s yearnings for both puppetry opportunities and a work that was an about-turn from their children’s theatre roots.

“So we had demons,” he said. “But what was even scarier? Everything around the production.”

2005 was not a great time for TFP. The company was waiting on an application for further funding. They had also sustained substantial losses from poor box office sales in 2004, forcing the company to do community productions, school workshop and evening performances, sometimes all on the same day. There was a lot riding on Devil to be a success.*

The programme cover for

2005 production of Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Image: C42 Repository.

On 6 Apr 2005, Devil premiered at The Arts House Play Den and it was unapologetically darker than anything TFP had produced before. Performed mainly in Chinese dialects, the play broached topics of death, sex and crime. The visuals exuded the bleakness of the characters’ fates, with stark metal frames (designed by Tze Chien) carving out the cramped spaces in the flat. Grim indoor lighting (designed by Lim Woan Wen) was created almost exclusively with practicals, onstage light sources. TFP’s puppetry also went from cheery to chilling – puppeteers played poltergeist-like demons that made objects in the flat fly about. A policeman puppet, at one point, is dismembered.

“We were all experimenting,” Tze Chien recalled. “Everything felt new, everything was unprecedented. We felt like we were on shifting sands because we weren’t sure if any of these things would work out in the end. But it was a point of no return.”

Devil was an unexpected smash-hit with multiple critics lavishing praise on it. In particular, Matthew Lyon of the independent reviewing platform Flying Inkpot would award the production an unheard-of five out of five stars. In his review, Matthew effused, “[The Finger Players] are now the company to watch in Singapore. They have given me the kind of play the dream of which first ignited my passion for theatre: one that is intelligent, layered, truthful, intense, utterly theatrical, and acted and designed to the highest standards.”

At the Straits Times Life Theatre Awards the following year, Devil swept nominations in five award categories, winning in three – Best Actress (Goh Guat Kian), Best Lighting Design (Woan Wen), and Best Director (Tze Chien).

Devil was TFP’s clarion call for its new, bolder approach to puppetry and theatre-making, and became a turning point in the company’s history.

In 2018, TFP underwent a strategic review, which led to a restructuring of the company the following year. Tze Chien relinquished his role as Company Director, and Myra Loke and Ellison Tan were appointed as Co-Artistic Directors. 2020’s Present/Future Season marks a transition between the old guard of TFP and new leadership, with a brand-new work, Peepbird, juxtaposed against three restaged shows helmed by senior core team members of TFP, one of which being Devil directed by Tze Chien.

Far from the immense uncertainty and pressure of those early years, I sensed an ease with which Tze Chien is re-approaching Devil, and unexpectedly, jubilation about stepping down as TFP’s Company Director.

“I can fully devote myself to creating art,” he gushed. “It already feels like I’ve retired! It’s been very liberating – I can do what I want, on my own terms. ”

Double Trouble

“I wanted it to be fun for me,” Tze Chien said on returning to Devil 15 years later. If anything sets the 2020 production apart from the original, it’s that it features two sets of characters.

Actors playing the same two characters either speak in unison, or in quick succession, or even deliver the same lines in different languages. And despite having two actors playing the same character, each actor performs their role a little differently from their counterpart. For instance, in Act 2, one actor plays the lascivious boyfriend vulgar and lewd when interacting with his girlfriend’s young daughter; his doppelganger adopts a cheekier and more caring portrayal, making room for an alternate story of misunderstood intentions.

It was simply a case of mathematics – there were only seven actors in the original 2005 production, and there is double the number of students. Instead of repeating the show with different casts, Tze Chien instead chose to have two casts performing at the same time.

“Because they are graded, I have to give each student something to play with,” Tze Chien explained. “But at the same time, I thought the play has enough room for some juxtaposition. So I experimented with the splicing, so that you can see the dynamism between the two sets of characters.”

I am reminded of Nine Years Theatre’s adaptation of August Strindberg’s Miss Julie in 2018, in which each of the three main characters was played by three actors at the same time. It made for a richer experience, but also one that was a challenge to follow.

Seemingly in anticipation of the difficulties audiences might face in Devil, the main characters are helpfully colour-coded – the actors in each act either wear red, blue or green T-shirts, and the two sets of characters within the same act are differentiated with a lighter or darker shade of the same colour. And if that wasn’t enough help, every T-shirt is labelled with the character’s identity and age.

In fact, everything on stage is labelled. A plain wooden stand downstage sports “Altar”. A human-shaped paper cutout is apparently an “Effigy”. Even the plastic chicken parts for the meal segments, if one looks really hard, have been stamped “Drumstick”.

At the end of rehearsals, the students gather around (masked and safely distanced) to hear comments from director Chong Tze Chien and stage manager Gillian Ong. Photo taken on 28 Oct 2020.

The labels leave little chance for confusion – when I return to rehearsals for a second time on 28 Oct, I am able to follow the show fairly easily.

The flat and corridor are marked out on the ground again, this time barely fitting into the smaller rehearsal studio. The sound design by Darren Ng, who also worked on the 2005 production, is ready. It’s a brand-new composition, I’m told, a soundtrack layering syncopated synthesised beats over plinking piano keys.

I watch the students run through the entire play again, and the rhythmic music greatly helps them with the snappiness of the choreographed prologue. The soundscape structures the play, clearly punctuating the beginning and end of each act with percussive notes and silences. The emotional arc of each act is also amplified by the score; I see the students’ performances similarly intensify.

“That was a good run,” Tze Chien comments to the students later. “But I also want to mentally prepare you for when we go into the theatre.” Stage manager Gillian Ong chimes in with warnings of how it will be far dimmer in the theatre and also stresses that everyone needs to be punctual.

At the end of the session, I’m helping to rip up the tape markings from the floor. It’s time for the production to move into the theatre.

Boot Camp

Tze Chien shared candidly that with the collaboration with NAFA, his main intent for re-staging Devil was more educational than artistic. For the students, working on Devil would be their first time working with a professional theatre company and performing in a full-length production.

“The actors’ bodies are young, so there’s no way for them to be performance-ready overnight,” Tze Chien said. “I think of the semester with TFP as a boot camp, to just drill them, so that when they graduate from the programme, they have a taste of professional-level acting.”

Marcus Kang, one of the student actors, plays the role of the pervy boyfriend in Act 2. He was really nervous to be working with a professional theatre company. He shared, “I thought they would be strict. I thought I couldn’t be myself. But I later realised I had to open up and show them what I can do.”

“I had the same thinking as Marcus”, his classmate Nor Sherina Binte Mohd Zailani, added. “I thought being professional means whatever the director says, you must follow. No talking back, just listen to them. But I love how they give us to opportunity to speak about what works for us and what doesn’t.” Sherina plays the wife who admits to committing adultery in Act 3.

Devil is truly a devil of a play for fledgling thespians to work on. Not only did the students have to grapple with a text first performed when most of them were still in kindergarten, they also had to plunge head-on into physical theatre and object puppetry, areas which they had not much experience in.

In preparation for the grueling demands of the play, the students spent three weeks exclusively with assistant director Chong Gua Khee at the beginning of the semester in Aug. She shared, “I wanted to work with the students on their body awareness. How well are you able to fill the space? How precisely are you able to start and stop? That’s about body awareness. For more inexperienced performers especially, the extremities like the hands and toes, they’re not fully aware of them.”

Gua Khee put the students through their paces with a range of exercises to strengthen and condition their bodies, and to sensitise them to moving onstage.

“I remember the exercises fondly,” Sherina said. “You imagine you’re a bodyguard and then you hear something. Or imagine you’re stepping on sand. It heightens your senses and your body immediately reacts.

“I love it! It’s really creative and it helped with my physicality, because I’m not really a physical person.”

Gua Khee also wanted to empower the student actors to be critical about their own and their fellow classmates’ performances. Adapting from Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process method, Gua Khee regularly had the students give constructive comments on themselves and to each other.

“It’s about getting feedback that makes you want to go back to work. And I think that is absolutely crucial,” she said. “For that, the artist needs to have the ownership and awareness of the material.”

The NAFA students had to come to grips with physical theatre, object puppetry and an enigmatic script within a few short months. Photo: The Finger Players.

To grow that sort of confidence in welding the play, the young students had to dive deep into Devil‘s 15-year-old text, which Tze Chien admitted, can be rather enigmatic. He said, “I wrote the play in a way that is deliberately very sparse, which means the words cannot carry the play; the actors have to carry the play. They have to do a lot of work as an actor to make sense of what the lines mean in context, in every single moment.”

“When I first saw the script, I didn’t really understand what’s going on,” Sherina said. “I was like what is this upgrade? Why are they fighting? And suddenly they’re eating bee hoon?”

“We had to do a lot of research, and we had to analyse the script for subtext and purpose,” Marcus added. “It took me a really, really long time to understand the subtext of some of the words.”

Sherina and Marcus shared that beyond having to go through the script repeatedly with a fine-tooth comb, the class had had many discussions outside of rehearsals over Zoom to discuss the characters and stories in the play, especially to ensure some distinction between the two sets of characters.

Between getting their bodies ready and immersing themselves into the minds and lives of Devil’s characters within a few short months, the students really had to step up their game. Sherina reflected, “After applying what I learnt from Gua Khee during those first three weeks, and the notes that Tze Chien had given me, I see myself improving. This experience has changed me – I feel like I’m quite good at this and I’m getting better every day.

“From the beginning to now, there has been so much change. Previously, I could see some of us holding back. Now, as a class, we’ve actually done so good.”

Something Old, Something New

I’m almost shivering with anticipation entering the studio theatre on the evening of 6 Nov – Devil would be my first live theatrical performance since theatres closed back in March. Besides me, there are a handful of invited guest in the house, and we’re spaced extremely far apart. We are told strictly not to applaud or make any sounds during the livestream.

As the lights fade to black and Darren’s evocative soundtrack rolls in, I feel the hairs of my arm stand. The lights come on and I see Woan Wen’s lighting design for the first time, an assortment of naked bulbs hung sporadically across the stage. Tze Chien’s new set – illuminated in morose shades of red, blue and green – comprises ropes hung vertically from the rig to bring the floor plan on the ground into sharp relief.

The prologue begins. A karang guni man wanders the corridor forlornly shouting for contributions. Soon after, more and more characters spill onstage in perfect timing. The actors, perhaps fueled by nerves, have found an intensity in their performances I’d not seen till now. The prologue escalates to a frenzy of movement, voices and sound, and then – blackout.

Although I’d only been following the production for one short month, in the momentary stillness before Act 1, I find myself silently rooting for the show to run smoothly, for the students’ success as they venture out into the world, for seasoned artists opening new chapters, and for a company to discover its desired new lease on life.

By Daniel Teo

Published on 20 Dec 2020

*Before Devil, TFP had staged 2004’s critically-acclaimed Furthest North, Deepest South, based on the story of the eunuch admiral Cheng Ho. But Tze Chien considered that production a “soft launch” for the new TFP, with production credits shared with collaborating company Mime Unlimited.

This article is part of the C42 Documents: The Present/Future Season series.

Centre 42 documents the creation process performances of the four productions in The Finger Player’s (TFP) The Present/Future Season. This documentation partnership with TFP aims to capture the inner workings of staging a production, illuminate the working relationships between practitioners and students, and create a textual record of the performance. Each production is documented by two writers, one focused on the performance-making process, and the other on the performance itself. The Present/Future Season was presented by TFP in collaboration with Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), and ran from 7 Oct to 8 Nov 2020.

C42 Documents: The Present/Future Season

[Process] Of First Flights and Transformations: Documenting “Peepbird”

[Process] What is Love?: Documenting “Love is the Last Thing On My Mind”

[Process] The Art of the Seamless Transition: Documenting “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”

[Performance] “Peepbird”: Decay and transformation

[Performance] “Journey to Nowhere”: Subversive, political take on a renowned classic tale

[Performance] “Love Is the Last Thing on my Mind”: Simple, poignant reminder to love”

[Performance] “Between Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”: From stage to screen