The ominous and dim look of Peepbird. In the background, tall panels threaten to fall over. Jo Kwek, fully decked out in black, sits on a bench. Photo: The Finger Players.

It feels invigorating stepping into the Esplanade Recital Studio on 7 Oct 2020. I am here for Peepbird by The Finger Players (TFP), one of the first few plays allowed to be staged under the National Arts Council’s pilot for the resumption of live performances following the closure of theatre venues since April. With the number of COVID-19 cases dwindling in Singapore, the theatre scene can take tentative steps towards normalcy with the implementation of safe management measures. I am excited at being able to watch a play live again, but it is a bittersweet moment, knowing that life—and theatre as we know it—has had to change, perhaps irrevocably.

In Peepbird, a similar ambivalence seems to be embraced, something I find myself musing about as I gaze upon the set in its entirety for the first time. Something feels ‘off’ – the looming concrete-grey panels on stage left are tilted precariously at an angle, barely standing if not for the almost invisible cables that hold it up. A chunky, dusty park bench sits off-center. The cool hues of the angular concrete set are juxtaposed against the earthy tones of the old tree that sprawls across the front of the stage. Despite the implicit discomfort from this lopsided set, the tension is apt. It captures the precarity of hanging in the balance, the same breathless anticipation of being on the cusp of transformation, in times a-changing.

Taking Flight

Peepbird is written by Ellison Tan and directed by Myra Loke, the newly-appointed joint artistic directors at the helm of TFP since April 2020. The announcement of their succession came as a pleasant surprise to the theatre community at the end of 2019, although the duo had already taken up artistic leadership of the company since March.

The Present/Future Season, which runs from 7 Oct to 8 Nov 2020, is TFP’s first major endeavour since its restructure and comprises four productions presented in collaboration with the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). The other core team members of TFP — Chong Tze Chien, Oliver Chong and Ong Kian Sin — are directing three pieces from TFP’s repertoire, performed by the graduating NAFA students. The fourth production, Peepbird, is the only new work, and the maiden production of Myra and Ellison in their new roles. Performed by actors Jo Kwek, Vanessa Toh and Al-Matin Yatim, Peepbird is a tale of a woman who finds herself so moved by the death of a crow that she subsequently transforms into one.

The premise reminds me of a simple Aesop fable or even a dark fairytale, but its meaning and experience are far more nebulous. For one, the play is non-verbal, employing instead a combination of puppets, costumes, movement and sound to tell the story. It also cycles through multiple transformations of the actors from human-like characters to non-human birds and puppets. These transformations are both gritty and magnificent, prompting the audience to interrogate the notion of an ever-changing identity.

These themes of transformation and identity can easily be traced back to the larger season, Ellison and Myra explained during my Zoom interview with them just three days after the show wrapped.

“Present/Future is especially meaningful because we are creating our own show, while our mentors are creating with these young people. At the same time, we are mindful that seven years ago, we were them,” said Ellison, referring to how she and Myra had taken on apprenticeships at TFP in 2014. I find it comforting that besides recognising the parallels in their own journey of learning, Myra and Ellison have also chosen to encourage the students to “move towards the future together” in uncertain times, as articulated in the season programme book. The imagery of little hatchlings leaving the nest and taking flight is not lost on me.

Haunting Visions

Where did the strange idea for Peepbird come about? As it turns out, Myra had her own unexplained, prior preoccupation with the humble crow.

“For many years, I’ve had people tell me about their encounters with crows. I also read stories online and I would save them in a folder on my desktop,” she said. “I think of the visceral sensation of walking down Orchard Road in the evenings. You can hear the crows as if they are right by your ear, but you cannot see them. You literally cannot see them at all.” That vividly terrifying experience of unseen swarms sparked many a creative thought for Myra, including the haunting vision of a woman transforming into a crow.

Jo Kwek wears a textured full body costume with removable wing appendages fastened on both arms. Photo: TFP.

In late 2019, the duo was brainstorming for ideas for the 2020 TFP season. Myra handed her research to Ellison, along with several excerpts she had written. Ellison immediately saw herself in the Woman.

“I really resonated with the idea of a destabilised identity. We had just stepped into this leadership position, and many times I felt like I had to change to suit the space I was in,” she disclosed. “I felt very affected by a huge shift in identity, so the Woman was very clear to me.” That personal experience, along with Myra’s image of the crow woman, crystallised their ambition for the work.

When Ellison began writing the script for Peepbird in February 2020, she quickly ran into several roadblocks, including having to find the most appropriate voice for the work.

“There’s literally no precedent in Singapore as to how anyone has ever written a script for a non-verbal puppetry play,” Ellison said. Her early attempts focussed largely on the transformation of the Woman, but she was well aware there was something lacking.

“A piece of feedback I’ve gotten many times before is that I’m always writing events. After the event happens, there’s usually nothing else. And I completely agree!” she said good-naturedly.

Ellison also penned some physical scores, but Myra felt that they left little room for experimentation. The two ended up having a long and serious conversation to clarify the character of the Woman and the aims of the work. They also consulted the design team, who suggested Ellison write a script that read more like a novel so there would be more opportunities for creative responses.

Then in April, Circuit Breaker happened. As the nation shut down and life ground to a halt, being alone with her thoughts gave Ellison the opportunity to experiment with a new way of writing.

“Every night at witching hour, I harnessed my actor side. I would turn off the lights in my room and speak into my phone’s voice recorder as if I was the Woman,” she shared. “It was like an audio diary of those two months of Circuit Breaker.”

“It was a bit scary,” she recalled, laughing at the memory. “Listening to the meditative, low buzz of my own voice saying things I don’t remember saying.” But as creepy as it was, the hard work paid off – Ellison was able to use the material from the audio diaries to piece together a performance text.

The end product is an emotive, prose-like text full of imagery, visual and aural word play. But because Peepbird itself was going to be non-verbal, the text became more of a launch pad for Myra and the designers’ innovations rather than a strict guide.

New Puppetry

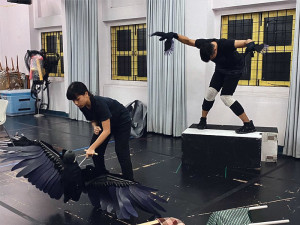

Vanessa and Matin rehearsing a scene with two different kinds of puppets — one that fits on the hand like a glove and another, a marionette.

I am curious that they would go through the trouble of refining the performance text to this degree and yet choose to stage an entirely non-verbal work. I prod a little deeper for the rationale behind their direction.

“Puppeteers are usually quite expressive and emotive, so when there’s text involved, they become even more visible,” Ellison explained. “It’s not bad or anything, but we just want to shift it so that the puppeteer and the puppet becomes a more cohesive entity in performance.”

Myra and Ellison are so invested in this inquiry that they decided following Peepbird, their trajectory for future TFP works will be entirely in the realm of non-verbal puppetry performance.

I think back to the Peepbird rehearsals I had the good fortune of sitting in on in late September and am reminded of how different it felt to have all the scenes run in silence. It was subtle, but the silence made the little things that much more vivid: the soft rustling of costumes, actors shuffling along in the TFP studio, with designers humming in contemplation at the side and my own muted and sporadic clacking of keys as I tried to take notes on my laptop quietly.

In the silence, I heard – and saw – the puppet-puppeteer unit much better, from the strategic breathing patterns of the performer-puppeteer, to the soft, stiff, filmy and fluffy materials. I could almost perceive the hands that wrought and styled the puppets and costumes too, as the different textures and materials jiggled, flapped around and fanned up and down. The silence made materiality, and the combined efforts of all the collaborators, stand out.

Myra had encouraged the designers – puppet designer and maker Loo An Ni, costume designer Max Tan, and sound designer Darren Ng – to have their own artistic interpretations of the text, giving them free rein over whatever they wanted to design.

“It’s like setting my own challenge, guessing how my designers would interpret the piece [in their work] and how I can use that in the show,” Myra said. As each new puppet and costume design came through the doors, she spent long hours outside of rehearsals studying them, exploring the textures, movements and the material properties of the items.

To highlight the puppet and puppeteer as one unit, the team employed a straightforward but ingenious method – a suite of designs the actors can both hold and wear. That way, the performer themselves could become the objects of interest, rather than just manipulate them.

When worn, the pleats of the white bolero bounce and shimmy, reminding one of feathers on a proud bird. Slumped over with the pleated bolero down, Vanessa appears to be merely a defeated character. Photo: TFP.

“I think people would tend to say there’s very little puppetry in this piece,” Myra noted with a chuckle.

I can see why it would appear the case – many of these wearable pieces look very unlike any conventional rod and string puppet. They range from wing appendages that are fastened to Jo’s arms as she transforms into the crow, to a flat grey suit made of thick felt that distorts Matin’s own silhouette and makes him appear to emerge from a concrete slab panel in the background.

In another instance, Vanessa wears a white bolero pleated in layers for a scene where she appears to be both a beautiful bird and a sophisticated lady who grows frustrated with her outwardly appearance. She slips between the multiple states, stripping off her high heels and putting them on again as she totters across the stage. The layers in the soft and light fabric make the bolero bounce with Vanessa’s movements, an effect Myra affectionately called “抖抖” [Mandarin for “tremble”]. The trembling fabric has a life of its own, suggesting fluffy feathers, although Vanessa’s character is still visibly human.

Pieces like the grey suit and the white bolero exemplify the work’s themes of transformation and identity, blurring the lines between man, object and bird.

Becoming One

“Peepbird is a representation of our philosophy when it comes to puppetry,” Myra explained. “It’s that pure commitment to the object you are holding in your hands. That devotion, that willingness and that one-to-one connection with it, where the puppet and puppeteer can feel like one body.”

This ‘one-ness’ of bodies and energies is exemplified in a key scene in Peepbird where Jo Kwek as the Woman metamorphosises into the crow. It is a powerful and important sequence that the actors drilled over and over again during rehearsals to get just right.

During a rehearsal, inside the brown fabric manipulated by Matin and Vanessa, Jo writhes and struggles, undergoing her metamorphosis.

A large, stretchy brown fabric, welded by Matin and Vanessa, slides over Jo, enveloping her body like an amniotic sac. Stripping away the outer layer of her costume from inside the sac, she flails and recoils as the crow takes over her human form. There are three actors in this scene, but the tensile fabric is the fourth with its own life force, resisting the grip and pull of the actors and sometimes slipping out of their hands.

They move with the fabric and each other, timing their stretching and contortions, to keep the energy of the entire mass continuously flowing. I see only one pulsing entity – the human performers, wispy through the sheer fabric, bringing the lifeless material to life, yet also swallowed up by the transformation themselves.

I cannot shake off the twin sensations of discovery and danger that Peepbird manages to evoke. It is being caught in the liminal space between imagination and reality, human and object, man and bird.

Throughout the journey of Peepbird, there is a sense of being on the cusp of great transformation and change with its brave explorations of new ways to write, create and collaborate. For Myra and Ellison, as freshly-hatched leaders with new wings fastened on, this is only just the beginning of a long winding path.

By Lee Shu Yu

Published 20 Dec 2020

This article is part of the C42 Documents: The Present/Future Season series.

Centre 42 documents the creation process performances of the four productions in The Finger Player’s (TFP) The Present/Future Season. This documentation partnership with TFP aims to capture the inner workings of staging a production, illuminate the working relationships between practitioners and students, and create a textual record of the performance. Each production is documented by two writers, one focused on the performance-making process, and the other on the performance itself. The Present/Future Season was presented by TFP in collaboration with Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), and ran from 7 Oct to 8 Nov 2020.

C42 Documents: The Present/Future Season

[Process] Of First Flights and Transformations: Documenting “Peepbird”

[Process] What is Love?: Documenting “Love is the Last Thing On My Mind”

[Process] The Art of the Seamless Transition: Documenting “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”

[Performance] “Peepbird”: Decay and transformation

[Performance] “Journey to Nowhere”: Subversive, political take on a renowned classic tale

[Performance] “Love Is the Last Thing on my Mind”: Simple, poignant reminder to love”

[Performance] “Between Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”: From stage to screen