In colonial Singapore, English literacy among the Asiatic population – Chinese, Malays and Indians – was alarmingly low. In a 1935 report in the Malaya Tribune, the 1931 population census found that:

…over six-sevenths of the native population are unable to decipher [English] street signs and advertisements and even, in most cases, to read the names of the street.

Source: The Babel of Tongues in Singapore. In Malaya Tribune (17 October 1935), http://tinyurl.com/yavgn9f7

However, among the three largest ethnic groups in Singapore, the Indian population led the way in English literacy. The same 1931 census report found that 14.3% of the Indian population were literate in English, compared to 10.6% and 7.0% of their Chinese and Malay counterparts respectively.

While English literacy can refer to learning English as a second language in a vernacular school as well as receiving an education where the main language of instruction was English, Indian children in early twentieth century Singapore were more likely to go to an English school than an Indian vernacular school, especially among the Tamil-majority.

Tamil education in Singapore began with the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles who needed English-educated Indians with the knowledge of Tamil. This led to the formation of Anglo-Tamil schools where Tamil was the medium of instruction and English was also taught.

In later years, however, interest in learning Tamil as a first language declined as English-educated parents preferred to send their children to English-medium schools.

As early as 1957 there were ten times as many Indian children in English schools as in Tamil schools. This showed that the Indian population valued English education, more than education in Tamil as the first language.

Source: Importance of learning one’s mother tongue. In The Straits Times (27 August 1982), http://tinyurl.com/yaeaytmp

The Indians are, it is regrettable to have to say, perhaps the community here who have not taken any interest in their national languages. The Penang Indians are more keen on this subject, as evidenced by the fact that they have already over thirty Tamil schools in that Settlement. Singapore Indians are lagging far behind. Maybe they are of opinion that English is enough for their children.

Source: Indian Education in Singapore. In Malaya Tribune (22 January 1934), http://tinyurl.com/ybg75yv8

Popular accounts of this phenomenon tended to cite a very pragmatic reason for the Indian population choosing English over their mother tongues – there were simply better job opportunities if you had received an English education than if you had graduated from a vernacular school.

This attitude of the Indian population was understandable as prospects in the employment field were better for the English-educated school leavers than for those who came out of Tamil schools.

Source: Importance of learning one’s mother tongue. In The Straits Times (27 August 1982), http://tinyurl.com/yaeaytmp

I am a Tamil with a [sic] little knowledge of my mother tongue. There are many Tamil parents here who have not taken much interest in seeing that their children study the language. This is a great pity, and is unjust to the children. When I compare other communities with mine, I have to admit that the Tamils are at the bottom of the list. There is no other community in the world that despises its own mother tongue as does mine in this place…

It is plain that Tamils are sending their children to English Schools only for the purpose of obtaining jobs in the Government, or in firms, or anywhere, and not to obtain knowledge…

Source: The Tamil Language. In Malaya Tribune (17 February 1930), http://tinyurl.com/yb347h6v

An English education in colonial times did indeed have its advantages – more Indians were able to occupy higher-ranking positions in schools, hospitals and even government.

Historically, Indians were the first non-white population in Singapore to acquire a high standard of English. Many Indian families have used English exclusively as the home language for more than a generation. In the top ranks of the civil service and the professions (doctors, schoolteachers and principals), in the years immediately after independence, Indians were over-represented.

Source: Multiculturalism in Singapore: an instrument of social control by Chua Beng Huat, http://tinyurl.com/y8brh2jr

The promotion of English as a language to unite the various ethnic groups existed even during colonial times. But it was the People’s Action Party, which came into power in 1959, that fervently pursued the idea of a bilingual nation and English as lingua franca. Subsequent national policy decisions cemented English as a first language of the nation and the language of instruction in all schools.

English literacy rates in all three major ethnic groups rose steadily as all children in Singapore had to receive an education in English, with a mother tongue as a second language. The 2010 population census found that among Singaporeans aged 15 years and over, English literacy rates were 87.1%, 77.4% and 86.9% among the Indian, Chinese and Malay resident populations respectively.

If the adoption of English minoritises non-English speaking Chinese, it has also simultaneously eliminated the privileges of Indians prevalent during colonial days….once English-language education was available to all through the national education system, the over-representation of Indians in the civil service and professions disappeared. By the sheer statistical weight of making up over 75 per cent of the population, top civil servants were almost all ethnic Chinese within twenty years.

Source: Multiculturalism in Singapore: an instrument of social control by Chua Beng Huat, http://tinyurl.com/y8brh2jr

With all ethnic groups receiving education in English, the local Indian population no longer had the linguistic advantage it once had during colonial times.

By Daniel Teo

Published on 26 Oct 2017

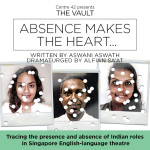

The Vault: Absence Makes the Heart… traces the presence and absence of Indian roles in Singapore English-language theatre. Written by Aswani Aswath and dramaturged by Alfian Sa’at, and featuring the actors Rebekah Sangeetha Dorai, Sivakumar Palakrishnan and Grace Kalaiselvi. Find out more here.