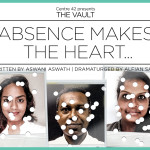

“The Vault: Absence Makes the Heart…” stars local Indian actors (pictured from left to right) Rebekah Sangeetha Dorai,Sivakumar Palakrishnan, and Grace Kalaiselvi. It’s happening at Centre 42 on 28 & 29 October 2017.

“Ramesh Panicker… R. Chandran… Who else?” Singaporean playwright Alfian Sa’at was sitting in the Centre 42 office on a cloudy Monday morning, trying to list established local Indian stage actors off the top of his head. “They’re very good, but we keep going back to the same actors over and over again. Or we import them from Malaysia – I mean, Jo Kukathas is everywhere when we’re looking for Indian actresses, right?” he grins.

Alfian is no stranger to talking or writing about topics that are considered taboo. Over the last two decades, he has discussed politics in his poetry collection A History of Amnesia (2001), sexuality in his plays The Asian Boys Trilogy (2000, 2004, 2007), and race and religion in Nadirah (2009), to name just a few examples.

And now, he’s setting his sights on something that he feels is absent from the Singapore stage – Indian representation. The idea came when Alfian initiated a casual gathering for practitioners to come together to talk about diversity on the Singapore stage. At one point, veteran director Alec Tok expressed his sadness that they were having that discussion that day, as there used to be many wonderful English language plays with complex, nuanced Indian characters in the pre-2000 years. It occurred to Alfian that there is a vast body of work in the Singapore theatre canon that many practitioners have either forgotten about, or have no knowledge of, which might shed some light on the way things were for ethnic minority actors back then.

To explore this, he proposed to create a work under Centre 42’s Vault programme, which will examine the trajectory of Indian roles throughout the history of Singapore English-Language Theatre. For him, the Vault is the perfect platform to revisit some of these older plays. “I’ve been to a few of the Vault presentations, and I must say I like the kind of work that is produced in terms of examining the archives, in terms of taking a look at the theatre history that we have. I somehow feel that we don’t do that enough,” he says.

Acknowledging that the story of Indian representation is not necessarily one for him to tell as a Malay playwright, he teamed up with local Indian actors Rebekah Sangeetha Dorai, Grace Kalaiselvi, and Sivakumar Palakrishnan, and invited Aswani Aswath – the young resident playwright at Buds Theatre Company – to write the script for the Vault project. Alfian himself assumes the role of the dramaturg. The resulting piece, titled The Vault: Absence Makes the Heart…, will be presented at Centre 42 on 28 and 29 October 2017.

Chicken and egg problem

Alfian Sa’at. Photo: Daniel Teo.

To get the research process started for Absence, Alfian assigned each actor a period to focus on. “Each actor had the responsibility of going through particular decades [of Singaporean plays] in search of the elusive Indian actor,” Alfian explains with a wry smile.

Soon, they found that Alec was right – Indian characters weren’t so elusive in plays written between the 1960s and 1990s after all. They found Sheila Rani and Baram in Lim Chor Pee’s 1962 work Mimi Fan (which is often hailed as the first English-language Singaporean play), and they found Reginald Fernandez in Robert Yeo’s Are You There, Singapore? (1972). There were still notable and challenging roles written for Indian actors in the 1990s, such as Vinod in Haresh Sharma’s Off Centre (1993) and Nisha in Elangovan’s Talaq (staged in Tamil in 1999 and translated into English in 2000, although the English performance was eventually banned). But there is a noticeable decline in the number of plays with Indian actors after that.

So where did the Indian characters – and the talent pool of Indian actors – go?

To find out, the team spoke with prominent Indian personalities from the arts community, such as Haresh, veteran practitioner and educator T. Sasitharan, playwright and actor Rani Moorthy, actor and singer Jacintha Abisheganaden, and director and screenwriter K. Rajagopal.

“So what we discovered in our interviews is that in the early days, there were many Anglophone Indians. That is specific to the history of the British Raj in India,” Alfian reveals. “They were great debaters and orators, and just really good in English lah. So going into theatre came naturally for a lot of them. It’s a stereotype, but the gift of the gab, the particular eloquence in English, was associated with Indian actors. And they got cast in a lot of plays.”

What changed was Singapore’s language and education policies.

After the People’s Action Party came into power post-Independence, the new government declared that English should be used as the lingua franca of Singapore. The bilingual policy was officially introduced in 1966, and all students were taught English as their first language by 1987.

“So suddenly the learning of English became available to everyone, no matter what your race was. And the edge that these Anglophone Indians had when it came to the English language wasn’t there so much anymore,” says Alfian. “So part of the reason [that Indians became less prominent on the Singapore stage] was also due to changes in national policies, the education system, and shifts in the language environment.”

He also notes that since Singapore theatre is dominated by social realist works, it’s not surprising that many roles in these naturalistic plays are now written for the English-speaking Chinese majority. And herein lies what he refers to as the chicken-and-egg problem. “There are not enough roles out there written specifically for actors with Indian ethnicity. It seems as if playwrights and directors think it’s going to be hard to cast, because there are very few really experienced [Indian] actors these days,” he explains. “But if you don’t give these newcomers the opportunity, then they won’t have [anything to put in] their CVs. So you do need to initiate a process where you will cast the newcomers, because this is what’s going to beef up their CVs over time.”

Indian 101

At the time that we interviewed Alfian for this article, Absence’s playwright Aswani had just completed the first draft of the script. It is roughly divided into two parts – the first is a sort of “Indian 101”, which addresses certain misconceptions about “Indian-ness”, and the second is a reading of excerpts from Singaporean plays that feature Indian characters, including some of the ones mentioned above.

But rather than a conventional reading of these works, Alfian also wanted to include a commentary from Sangeetha, Grace, and Sivakumar about how they would assess these roles as actors. So he invented what he playfully named the Palakrishnan-Kalaiselvi-Dorai test (or the PKD test for short). It is based on the Bechdel test, which indicates the active presence of women in film. For the PKD test, it is passed when 1) the play has at least one Indian character in it, 2) who is not used as a token or to fill up a quota, 3) and does not perpetuate stereotypes, such as Bollywood dancing or excessive melodrama. The idea is that the actors would perform the play excerpts, and then give them a score based on the PKD test’s criteria.

“I want the audience to get some kind of insight about what roles are considered nuanced and complex, and what are considered stock. I think if we can hear from these actors about what kind of roles they love sinking their teeth into, and what are the kind that they feel are quite cardboard, then maybe some of us can learn something from it,” says Alfian.

Apart from the performance presentation, there will be a mini exhibition in our Front Courtyard. It will comprise a series of portraits featuring the three Indian actors in iconic roles that are often played by their colleagues from other races.

“We wanted a photography component because I think as a minority person I find the image very powerful. As something that’s aspirational, as something that can disrupt dominant standards of beauty,” says Alfian. “It’s not a coincidence that certain things, such as a magazine cover featuring a black or Asian model, make the news and make a lot of people excited. So our alternative history photo exhibition consisting of minority actors in iconic Singaporean plays will, I hope, provoke some discussion about how we cast for our plays.”

His wish is that the conversations generated by the performance and the exhibition can collectively serve as a first step towards breaking the chicken-and-egg cycle. “One thing that I learnt [during my research for Absence] is that if we want to write Indian characters into our plays, we wouldn’t be introducing a new thing. We would actually be reconnecting with our own historical tradition,” he says. “I hear a lot of people saying – especially playwrights – like I don’t dare to write about Indian characters, because I feel I don’t have the authority to write about it. But how did someone like Ovidia Yu, for example, have the confidence to write about an entire Indian family in Round and Round the Dining Table? I mean there are ways to do it, absolutely. One way is to just do research – you talk to people and let them read and fact check your script. Otherwise, you workshop and devise with others.”

And by presenting this edition of The Vault together with his all-Indian team, Alfian shows that that can, indeed, be done. Here’s hoping that more theatre-makers will follow in his footsteps, and get one step closer to bringing more diversity to our stages.

By Gwen Pew

Published on 12 October 2017

Find out more about The Vault: Absence Makes the Heart… here, and join us at Centre 42 on 28 & 29 October 2017.