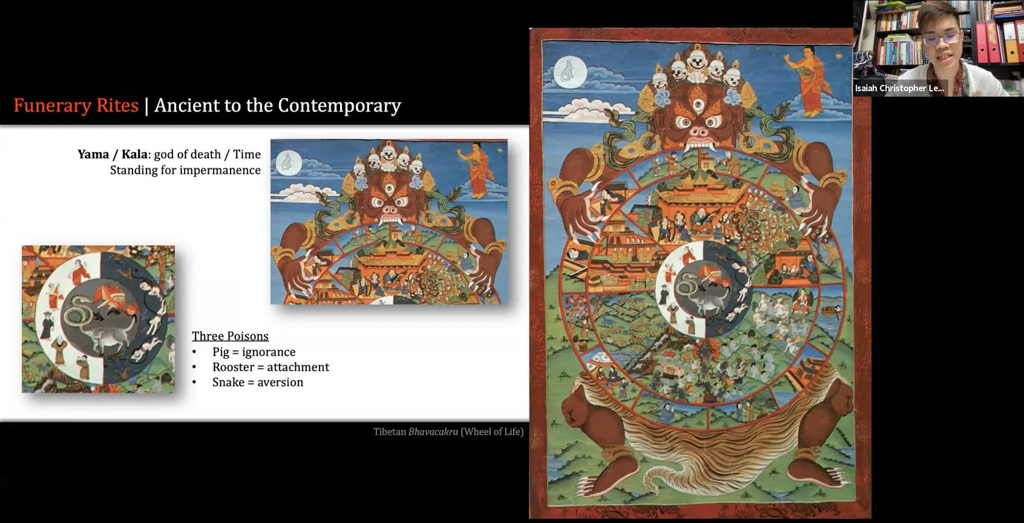

Isaiah introducing the Tibetian Bhavacakra (Wheel of Life), with the image of Kala, the god of death, standing for impermanance, amongst other concepts of life and death at The Vault Lite: A Whole New World? Artist-in-Residence Sharing.

“The responsibility for bringing about an enlightening situation is finally our own.”*

Everything flows into each other in the end; without the ancient scriptures that crystallised Vedic thought, there would not be an Asia we have come to know of today. Without the articulation of the trope of “neither nor”, a concept I borrow from the scholarship of the Vedas that partakes of the principle of “not to” to make sense of the seemingly paradoxical and incongruous elements of lived reality, there would be no Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. Without these ancient modes of thought, there would be no text that would eventually find its way into Tze Chien’s life and into his contemporary writing. The more I research, the more I realise how my ignorance will always outweigh my own limited knowledge conditioned my training and experiences.

This research process is just one amongst many that I hope to partake in throughout my life as an arts practitioner, for I strongly believe that art was never meant to be created, established, and interacted with within a vacuum. The artist is also an academic. The artist is also a thinker. The artist must be that. Through surveys and interviews that we conducted throughout this residency, the impetus to return to our modern modes of linear thinking in attempting to unpack Tze Chien’s work and reimagine a contemporary afterlife for it was far more tempting than expected. Our conscious decision not to simply regurgitate what scripturally seemed sound was part of this process of acknowledging the slippages that exist within current theological, artistic and academic discourses. In so doing, we at least glimpsed a transcendence of modern dualistic thinking and in the last stages of our residency came to grips with what it meant to dispense with dichotomic oppositions and rethink our own assumptions and presuppositions about death and loss.

Tze Chien’s work is at the heart of this journey. There will never be enough words, or the right words to capture how eloquent he is or how diverse his prolofic thoughts are. His humility was something that struck as a point of emulation, a jewel that reflected everything he believes in and everything he stood for. Just as all phenomena is conceived as components of a network of interconnected nodes containing and reflecting one another like a net of polished jewels as per the metaphor of Indra’s net standing for concepts of void or śūnyatā, and dependent origination or Pratītyasamutpāda in the Buddhist Avataṃsaka, or Flower Adornment Sūtra.

This exploration process was particularly generative in terms of what it yielded out of reimagining the meaning of loss in the context of a Buddhist worldview and its associative artistic legacies. In other words, what we eventually arrived at was an amalgamation of resources that now extend Tze Chien’s original work by furthering the exploration of Buddhist visuality in the set design, props, text and so on. The exploration also allowed us the space and community to gather feedback on our research methodology so that we could better cater the final script to represent a new generation of individuals based on their ruminations on death and loss.

Initially, I came into this residency having read the play and wanted very much to work on something that deals so pertinently with the aftermath of trauma. The final work, however, deviated from our initial proposal of looking at healing through the lenses of a contemporary pandemic. Rather, we narrowed the focus to rethink and re-envision a world that has become so used to loss, especially through the subversion of subaltern voices to give the dead characters a voice in our afterlife of ‘Poop!’.

One of the unexpected aspects of our exploratory journey was how the uneven the current scholarship is on Southeast Asian Buddhism provided both challenges and potentials for further discourses and artistic creations based on existing scriptures or frontiers of knowledge. Additionally, we found the results for our survey done on loss, grief and death particularly interesting because of the diverse range of responses from different Singaporeans aged 20-30+.

Ultimately, this entire residency and research journey has offered me deeper insight into the ways in which we might think about and conceive the arts and artistic practice in Singapore. It is perhaps this attitude of continually questioning existing notions of “art” and “Singaporean” works that we might be able to innovatively push the boundaries and limitations of our knowledge. Only through the liberation of previously hidden voices will new stories emerge and come into our contemporary canons of art. Thus bringing into light what was once unseen, to experience what had once been an illusion, and to listen to what was once unheard of.

Isaiah Christopher Lee, Reflections on Rehearsals for (Im)permanence

References

Peter D. Hershock, Chan Buddhism: Dimensions of Asian Spirituality (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), 4.

Rehearsals for (Im)permanence by Cheryl Tan & Isaiah Lee was developed under The Vault Lite: A Whole New World in respond to Chong Tze Chien’s play, POOP!. This edition of The Vault: Lite ran from January to February 2021. Find out more about The Vault: Lite and Cheryl & Isaiah’s work here.