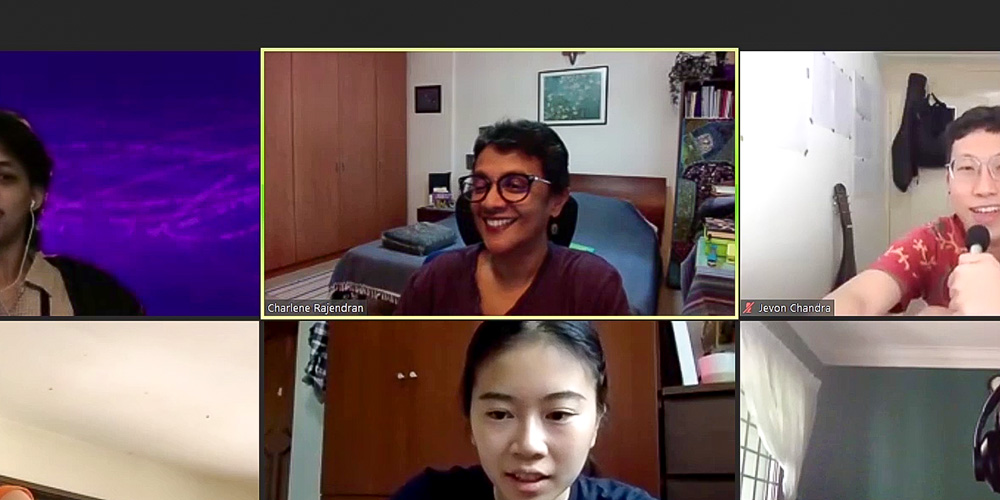

Charlene Rajendran facilitating a session of “Rethinking Practice and the Practitioner: Pandemic Purpose” on Zoom.

Charlene Rajendran has been teaching at the National Institute of Education (NIE) for the better part of two decades. As the most experienced facilitator of our nine-week online course titled Rethinking Practice and the Practitioner: Pandemic Purpose, I truly wasn’t prepared for her to make the following statement:

“I’ve now completed my first Zoom course!”

But I shouldn’t have been terribly surprised. The COVID-19 pandemic has upended most of our lives and sent us scuttling for cyberspace. Zoom, in particular, fast became ubiquitous, surging from 10 million daily users in 2019 to over 300 million in April this year. Out of necessity, we began spending large chunks of our day working, studying, socialising and living on the web conferencing platform.

Pandemic Purpose also ran during summer break, so Charlene had yet to conduct her NIE classes online.

When a beaming Charlene made her declaration, the window pane of faces erupted in applause. I, however, was left wondering what insights the seasoned educator might have gleaned from developing and conducting a course via web conferencing for the first time. We chatted a few weeks later – on Zoom, of course.

“On Zoom, everything is a lot less fluid,” Charlene tells me after a pause. She’s visible on my screen from the waist up, with a neatly-made bed behind her. I’d just asked her how teaching online differed from in the classroom, and I sensed that Charlene was still digesting the experience.

“People coming into Zoom – they’re a bit more silent. It’s a different dynamic that’s not as fluid,” she continues.

There is indeed a developing etiquette for Zoom users. People enter the room with their microphones muted. Some don’t even have their video cameras turned on. In large groups, everyone tends to keep themselves on mute when they’re not speaking.

Charlene also notes that time, too, is not as fluid in an online workshop: “We’re doing this activity for this amount time. There’s a lot less capacity to bleed into things, to let things emerge and come up.”

Breakout discussions, for instance, can be strictly timed – should the host wish, you could be booted out of a discussion room automatically when the timer runs out.

For someone who is more used to dealing with students in-person in a classroom setting, Charlene is very conscious about managing energy levels. And on Zoom, she noticed energy levels waning faster: “The demand for concentration and focus I think is much more than it would be if we were sitting in a room. The same people sitting in a room could probably keep going for three hours, maybe even four hours, but two hours is already pushing it on Zoom.”

“Zoom fatigue” is a reported phenomenon, describing a feeling of exhaustion after web conferencing. The most accepted explanation for Zoom fatigue is that that our brains have to work much harder to decipher verbal and non-verbal cues onscreen as compared to during face-to-face encounters.

All these issues could have posed huge problems for a course created to engage young performing arts practitioners in lengthy, intense discussions with each other. On her aims in Pandemic Purpose, Charlene says, “I wanted the participants to talk about, think about and reflect on their practice. And hear each other, listen to each other. And as a result, try and listen to themselves. I wanted to try as much as possible to make this encounter lead in that direction of becoming more reflective, becoming more aware of what you’re thinking and how you’re thinking, and becoming more willing to question and respond and interact at deeper and deeper levels.”

So what to do?

One of Charlene’s solutions for conducting her course on Zoom was relatively straightforward.

“It was really useful to have everyone’s camera on all the time,” she shares. “Except during breaks, because otherwise that really changes the dynamic. And mute mics only if there’s something noisy outside, but otherwise leave it on.”

To combat dipping energy levels, Charlene would change things up for the Pandemic Purpose participants every now and then. She’d throw in riddles and word games to break up a series of discussions. She calls these activities “energy pops”.

“People need variety!” Charlene explains. “It’s because the brain suddenly works differently and suddenly you free yourself of awkwardness and clumsiness. That kind of injection helps things to happen.”

Charlene also gave ‘off-line’ assignments to be completed in between the weekly course sessions. In one assignment, she had each participant take a walk outside and then write a letter about the experience to a fellow course mate.

“I think the letter was really about doing something we don’t usually do,” Charlene says. “You become more conscious of why you’re doing it and the strangeness of it, the unfamiliarity of it, as a mode to reflect.”

But the letter was more than just reflection – it was about creating a connection.

“You will be thinking about the person you’re writing to with slightly more consideration. So you’ve got a connection with somebody,” she elaborates. “Hopefully, when you come to Zoom, it creates a layer of connection, a sensing – you’ve had to sense this person in order to write this letter. And when you receive the letter, hopefully you feel seen, you feel sensed. It’s about their connection with you.”

All these and more were tactics Charlene employed to ensure rich conversations and interactions, even when the Pandemic Purpose participants couldn’t be in the same physical space.

But the thing is – are these tactics even all that different from the ones used in a classroom environment? Recall Charlene’s hesitation at the start of our chat – she is aware of making teaching online sound like a completely different kettle of fish.

“It’s the same even when you have people in the same room,” she admits.

Conducting a course entirely on Zoom, then, was more an opportunity for Charlene to take a good hard look at her own pedagogy: “In the classroom, I have these instincts from having done this for a long time. There are these instincts that are felt and one is not conscious of. In a way, doing this experience allowed those instincts to develop.”

Our conversation could have ended on that self-reflexive note, but sharp-witted Charlene wasn’t going to leave the virtual room without one last observation from her time facilitating Pandemic Purpose.

“I’ve never seen my face so much!” Charlene chuckles. “It’s really weird. But it made me recognise the performativity of teaching online.”

“So for the last session, I made sure to wear dangly earrings!”

By Daniel Teo

Published on 31 August 2020

Rethinking Practice and the Practitioner: Pandemic Purpose was an online course that took place from 17 Jun to 12 Aug 2020. Over nine weekly sessions, 14 young performing arts practitioners worked with facilitators Charlene Rajendran, Corrie Tan and Chong Gua Khee to hone critical skills as well as reflect on their practices in a post-COVID-19 world. The course was developed with support from the Asian Dramaturgs’ Network, and commissioned by National Arts Council Singapore. For more information, click here.