The Project Understudy Writing Team: (L to R) Isaac Lim, Dr. Robin Loon, Fong Chun Ming, Gabriele Goh, Eugene Koh, Olivia Vong, Matthew Fam

Collaborative writing can be hugely challenging. Without a strategy, writing a play in a group would just be a matter of whoever has the strongest pair of lungs, as was the case with the seven men who collectively wrote the 1971 play Lay By at the Royal Court Theatre in London:

“They sat down in a room with a big, blank piece of paper and all shouted out,” she reports. “The person who shouted the loudest had their line written down.” To make matters worse, Gupta chips in: “They had a woman secretary who wrote everything down for them.”

Source: This could actually work by Maddy Costa. In The Guardian (29 Nov 2006), http://tinyurl.com/jbwyvu7

For the seven writers in Project Understudy, they wanted to craft a sequel to Tan Tarn How’s Undercover together in a slightly less raucous manner. Titling the sequel Understudy, the writing team began writing at the start of 2016, finding their own strategies for multiple dramatists working together on one script.

In using all these strategies, the writing team was able to create a complete draft for Understudy in a few short months. The script is still in its early stages, but continuing to work on it together means that the team can pursue testing out and refining other collaborative writing strategies.

-

Write for only one character

From the beginning, the writers each picked one character and wrote only for that character. Four writers assumed established characters from Tan’s plays – Jane, Qiang and the Deputy (now called KK) from Undercover, and Derek from The Lady of Soul and her Ultimate “S” Machine. The remaining three crafted new characters from scratch, the protégés Sophie, Albert and Vikram.

By having to be responsible for only one character, each writer could explore his/her character in-depth. A character-centric writing process also allowed for the next few strategies to be employed.

-

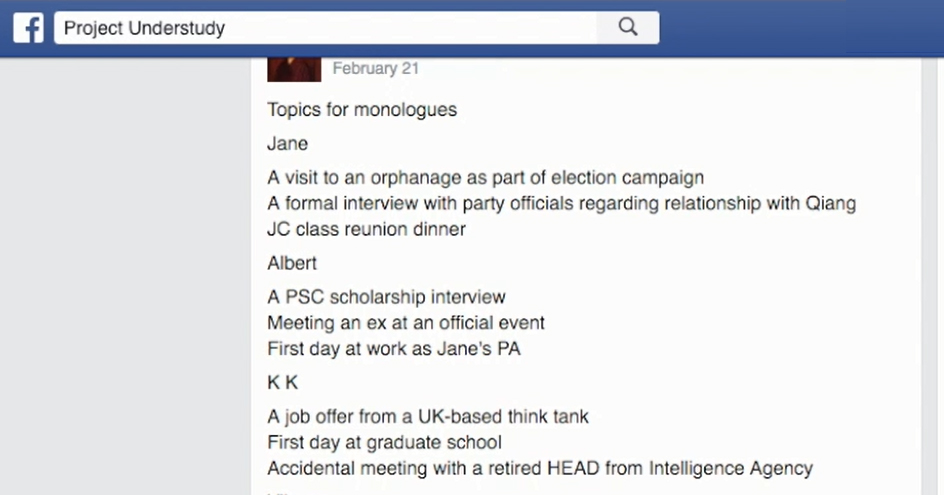

Write monologues for your character

I decided that for us to get into the character itself, I gave them six to eight scenarios for them to choose from, so they write a monologue – and some of these monologues are really good, they clarify the characters. And then after they read it out for everybody else to hear, so everybody who’s writing the scene also knows where the character is at.

Dr. Robin Loon, Project Understudy Writer/Chief EditorEach writer wrote monologues for their characters, which they would share with each other at writing sessions. Portions of the monologues were used in the first complete draft of Understudy.

This strategy resembles parallel construction, as used by education researchers Onrubia and Engel in describing their observations of collaborative writing in a classroom setting. The parallel construction strategy involves each group member completing a writing task on their own before contributing it towards the completion of the overall project.

For Onrubian and Engel, parallel construction is often employed in early stages of collaborative creative projects, in a phase they call initiation:

During the phase of initiation, the group members make their ideas public, without questioning those presented by others. Nor do they get involved in explicit processes of negotiation of meanings, so that the joint activity gets more of a character of sum of monologues than a dialogue. The phase of initiation includes all those forms of participants’ joint action that result in a first level of intersubjectivity of the definition of the task and what procedure to follow to carry it out.

Source: Strategies for collaborative writing and phases of knowledge construction in CSCL environments by Javier Onrubia & Anna Engel. In Computers & Education (2009), Vol. 53(4), pp. 1256-1265, http://tinyurl.com/hzz45bqFor the writing team, the monologues not only allowed them to individually explore their character’s motivations and idiosyncrasies, but also, in sharing the monologues, they could begin to see how their characters might possibly interact with other characters in scenes.

-

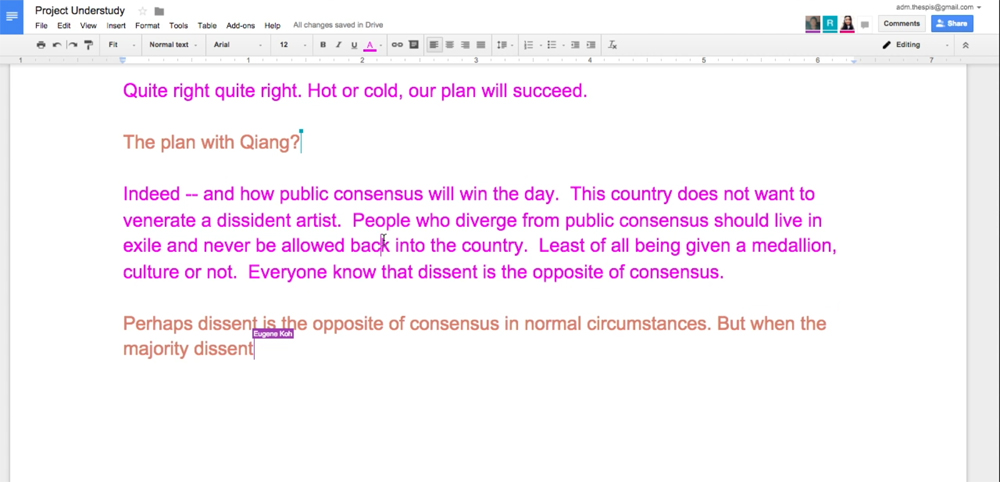

Take turns to write lines in a scene

There’re tables in the middle of the room and then we sit around the table. And instead of an improv session – there’s no acting – [we] just write.

Matthew Fam, Project Understudy WriterThe writers worked on each scene together. During their writing sessions at Centre 42, each writer was armed with a laptop logged on to Google Docs. Working on the same document, they took turns to create their character’s lines, akin to the improvisational work performed by actors in devised theatre.

Onrubian and Engel use the term sequential summative construction to describe this strategy. For them, this strategy encouraged a group to explore a topic together – exchanges between group members tend to be “turns of presentations and acceptance” with few disagreements as the group constructs the work accumulatively.

Business communication researchers Lowry, Curtis and Lowry call this strategy sequential writing: By taking turns to write, the researchers found sequential writing to be a simple and effective way for coordinating and distributing work between multiple writers.

However, the researchers highlighted one major disadvantage of sequential writing:

[…] this approach is often problematic without effective version control; otherwise, subsequent writers can easily override the work of others by making new changes. Source: Building a taxonomy and nomenclature of collaborative writing to improve interdisciplinary research and practice by Paul Benjamin Lowry, Aaron Curtis, & Michelle Rene Lowry. In Journal of Business Communications (2004), Vol. 41(1), http://tinyurl.com/hw4s4ug

To solve this issue, the writing team used the next strategy.

-

Assign one member as the editor

Dr Loon will start off by outlining the scene that we’re going to proceed on to do today, and tell us generally what we’re going to do, what our characters are supposed to be doing in the scene, what [their] function [is], how the dialogue’s going to go. Then we take it from there.

Fong Chun Ming, Project Understudy WriterDr. Robin Loon (who writes as KK), served as the Chief Editor of the project. In this capacity, Dr. Loon created the entire narrative arc for the sequel. At the beginning of each writing session, he laid out the objectives of the scene they were working on. He also edited the script generated by the writing team.

Having an editor on the team can be very helpful as he or she makes the final decision on the work and ensures the writing process moves forward. One example of an editor moving a work forward is Ezra Pound who edited T. S. Eliot’s seminal poem The Wasteland:

In short, Pound reduced the poem from over 1000 lines to its current 434. In the process, he focused and limited the poem’s message and eliminated a sarcastic tone. The critical view, with only the exception of a handful of scholars, is that Pound’s edited version is an undeniable improvement. Eliot, who was mentally infirm and hospitalized during the period of writing and revision of the poem, acquiesced to almost all of Pound’s revisions and suggestions. [Author of Multiple Authorship and the Myth of Solitary Genius, Jack] Stillinger brings attention not only the extent of Pound’s changes but connects the collaboration to an argument that the resulting text constitutes a co-authored work.

Source: Collaborative Literary Creation and Control: A Socio-Historic, Technological and Legal Analysis, http://tinyurl.com/z2pg8ff

By Daniel Teo

Published on 20 May 2016

The Vault: Project Understudy revisits Tan Tarn How’s Undercover and reimagines its sequel set in 2016 through a collaborative writing creation process. Conceived and edited by Dr Robin Loon and organised by NUS Thespis. Presented on 23 May 2016, 8pm at Centre 42 Black Box. Admission is free. Find out more here.