“Is ‘dramaturgy’ the new word that we’re all using, all the time? And in 25 years will I wear a perfume called Dramaturgy?” joked ArtsEquator’s Kathy Rowland at the Asian Dramaturg’s Network (ADN) Satellite Symposium in Adelaide in 2017. Her comment emerged in an open discussion about the way ADN had been handling the term. Having documented all of ADN’s activities in the past three years, I’ve noticed it’s been a recurring concern. And it’s important to ask ourselves what we mean by “dramaturgy”, especially since the term seems to have come into vogue since ADN’s inception in 2016, at least in Singapore.

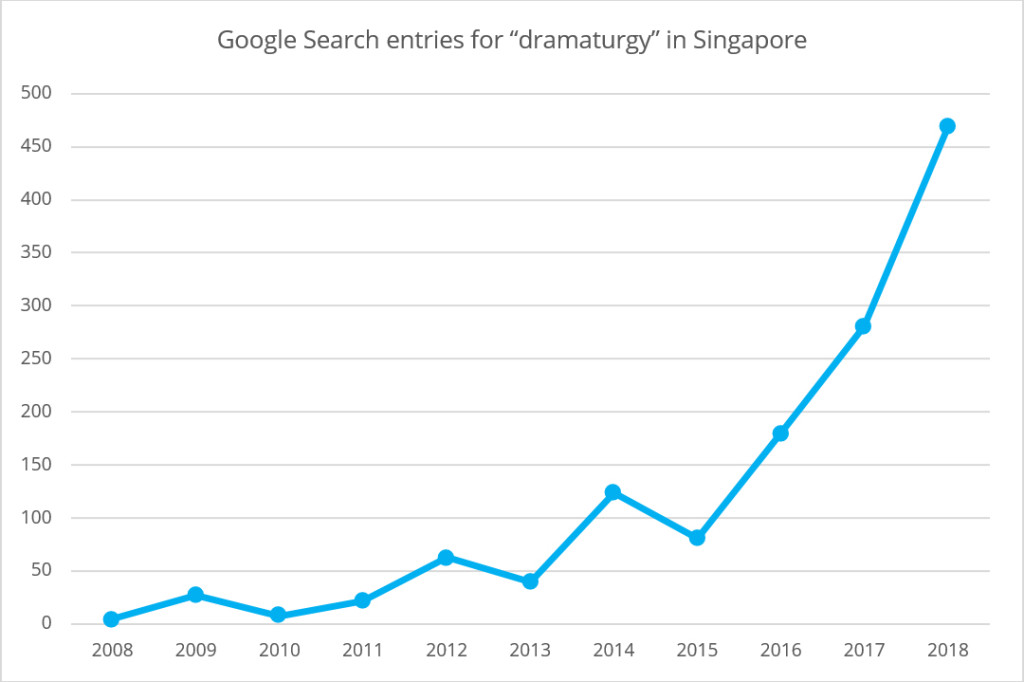

Looking at the number of Google Search entries in Singapore for the word “dramaturgy” (inclusive of all its variants like “dramaturg”, “dramaturgical”, etc.), there is a noticeable spike in the last few years. This surge seems to suggest that dramaturgy has become quite a buzzword in the local Interwebs.

I’ve also noticed more theatre productions in Singapore crediting dramaturgs, especially those by younger groups like Bhumi Collective and The Second Breakfast Company. A more established company, Checkpoint Theatre, has recently promoted its latest production using the phrase “directed and dramaturged with verve and sensitivity” in its publicity material. And in a student production by the Intercultural Theatre Institute in March this year, the dramaturg emerges at the start of the performance to preface what the audience is about to witness. At the State level, in its five-year plan for the arts in Singapore, the National Arts Council identified dramaturgy as a potential area for regional networking and sharing in the performing arts.

So what is dramaturgy? The origin of the word is credited to 18th century German dramatist Gotthold Lessing, who defined the term as “the concern with composition, structure, staging and audience from literary analysis and historiography”. This definition resonates with the idea of dramaturgs as literary managers and researchers, firmly ensconced in the areas of text and theatre.

But in the 20th century, some academicians – most notably rhetorician Kenneth Burke and sociologist Irving Goffman, began using the language of theatre to describe the individual and society. Viewing life as a performance, with a private self that exists “backstage” and a public self that performs “onstage”, dramaturgy then became a study of how humans interact with each other, individually and collectively.

ADN straddles these two understandings of dramaturgy, with one foot firmly in the performing arts and another in a perspective on society, seemingly comfortable in its fluidity. Kathy observes of the ADN proceedings in Adelaide: “It did, at times, feel as if the term was in danger of becoming so open and inclusive as to be emptied out of its meaning…”

A review of past ADN conference themes gives us clues to this amorphousness – “Mapping In, Out and About” and “Tracing Asian Dramaturgy”, not only engage with the geopolitics of the network’s eponymous “Asian”, but also situate dramaturgical practice within the performance-making process; while “Dramaturgies of the Social and Cultural” and “Dramaturgy of the Political” site dramaturgy in the larger context of society. But despite the themes, all ADN gatherings have engaged in explorations of both dramaturgy in performance and society. The multifarious discussions demonstrate a reluctance to view artmaking in isolation of its wider context, and consequently dramaturgy has to be considered with eyes on the micro and the macro as well.

Another clue to the fluidity of dramaturgy in ADN can be found at the very first discussion in 2016 at the inaugural symposium in Singapore, when Indonesian dance dramaturg and researcher Helly Minarti proposed the Indonesian words pendamping and penganggu as Bahasa Indonesian equivalents for the English “dramaturg”. Pendamping means “companion” and penganggu means “bully or disturber”. The dramaturg as penganggu has come up in almost every ADN gathering since, coming to represent the dramaturg as a critical proponent of an artwork, over the implied compliancy of the pendamping. The penganggu dramaturg is adversarial to the art-maker for the purposes of improving the work.

Dramaturgical thinking is then synonymous with possessing a critical lens. And if art draws its inspiration from humanity and society, then as a proxy of these, a dramaturgical perspective necessitates a betterment of the world through a deep examination of its structures and relations via an aesthetic frame.

But can there be rigour if a word seemingly lacks conceptual boundaries? With such an open understanding of dramaturgy, rigour perhaps shouldn’t come from or be enforced from the top, as that would curtail the range of discussions the network is able to have and the kinds of people who are able to speak.

Rather, rigour can emerge from how the individual dramaturg or performing arts practitioner makes sense of and practices dramaturgy. “You have to be rigorous with yourself in terms of the way you think of it. And the more rigorous you are, you can communicate a certainty that people can respond to. So in that space you’re actually creating a dialogue,” said Australian dramaturg David Pledger. “Dramaturgy as a word is a prism, through which you can enter from multiple directions. And that is a very rare thing for a word to provide.”

I recall once joking to a colleague, “So, everything can be dramaturgy!” And it seems, with ADN, that it might just be possible, and also opportune, to view art and the world through a dramaturgical lens.

By Daniel Teo

Published on 5 April 2019

ADN’s next meeting, part of the Singapore International Festival of Arts, is ADN Conference 2019: Dramaturgy and the Human Condition, from 25 to 26 May 2019 at the Festival House. Details and registration at asiandramaturgs.com/conference2019.