Framed, by Adolf, the second play in Chong Tze Chien’s “Hitler trilogy”, will make its public debut in June 2018. Photo: The Finger Players

Chong Tze Chien arrived at Auschwitz Concentration Camp in Poland on a cold, rainy morning in October 2015. He was there on a research trip that was funded in part by Centre 42’s Fellowship grant. By then, he had already written and staged Starring Hitler as Jekyll and Hyde – the first play of his planned “Hitler trilogy” – based on what he learnt about the period from books, films, and videos. But that did little to prepare him for the horrific stories that he would encounter at Auschwitz, which now stands as a memorial and museum dedicated to the victims who were murdered there.

The detail that he found most harrowing during his visit was realising that ordinary German people knew what was going on in the concentration camps back then. And that many of those who worked at the camps had no qualms about it, because it was safer to go along with the masses than to confront the inconvenient truth.

“You can imagine them [carrying out the killings] on a daily basis and being able to sleep every night because to them, it was like killing pests – it’s the natural thing to do,” says Tze Chien. “It’s easier to throw morality out of the picture, so you can claim innocence. But there are no innocent bystanders.”

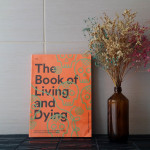

When Tze Chien came back to Singapore, he wrote the second play in his trilogy, Framed, by Adolf (then titled The Fuhrer’s Work), in three days. While Starring Hitler examines the dictator’s rise to power and the Holocaust that ensued, Framed takes place in a contemporary setting where truths can be easily constructed, sold, and bought. The story follows a woman who inherited a rare painting by Hitler from her Jewish grandfather, who had escaped the Holocaust by posing as a Nazi. She tries to sell the artwork to an academic, an auctioneer, and a businessman, with each character attempting to outwit the others by presenting their own version of the truth.

Looking back, Tze Chien sees that he has always been intrigued by the idea of truth. His very first play, Pan Island Expressway (PIE) (1999), is about a playwright who is arrested and interrogated when the scripted deaths of his actors become real. The interrogator then twists and misinterprets the playwright’s truths, and uses his own words against him.

The test read for Framed, by Adolf (then titled The Fuhrer’s Work), was held at Centre 42 in September 2016.

Arthur Kok, who reviewed the original production of PIE for The Flying Inkpot, wrote that “[h]ow the interpretation of one (the interrogator) is capable of reframing ‘truth’ (as James [the playwright] conceives it to be) is thus deftly addressed in PIE. How this interpretation and (re)presentation of ‘truth’ invents intentionality and responsibility are also powerfully foregrounded.”

That same tactic of reframing truths allowed Hitler and the Nazis to relabel racism as patriotism. And in today’s world, where truths have become easier to invent and construct than ever before, history seems to be repeating itself.

“We are now living in the Trump era, and these works [about Hitler] can’t be more relevant. Everyone has a platform to say what they want these days. They can do so without responsibility and without any consideration of others, by hiding behind an online avatar,” says Tze Chien. “What fascinates me is how uncanny the similarities are between 1930s Germany and what is happening in the world today. We are not living in a world that necessarily values objectivity. It’s about being a populist.”

He believes that we’re never able to really learn from the past because we lack self-reflexivity, and because we’re unable to envision the extent of tyranny that our fellow humans are capable of. Instead, we choose to see only what we want to see.

“What disturbs me is that when you push forth your own opinions as the objective and absolute truth, that’s where bullying becomes the status quo. And when everyone insists that they are right, there can be no more room for conversation after that,” he says.

And yet, he also admits to feeling a personal connection to the fact that Hitler was, like himself, an aspiring artist in real life.

“You know how artists can be egomaniacs. We’re all Type A personalities who are obsessed with creating our own vision, and presenting it to the world,” he says. “There is always this tension between the artist’s ego and his/her predilection for truth; when the former trumps over the latter, vanity is the result.”

There are always many sides to a story, and Framed is Tze Chien’s attempt to look at that particularly dark period of history from another perspective. It’s apt that he does so through theatre, where different characters can present various realities to the same group of people.

So what would you, as an audience member and an individual, choose to believe?

By Gwen Pew

Published on 3 April 2018

Find out more about Framed, by Adolf in our earlier interview with Tze Chien here, and by following The Finger Players’ Facebook page here, and catch the show at Victoria Theatre from 15 – 17 June 2018.